Should games stay true to their iconic elements that we fall in love with? Or should games be more inclusive even at the cost of what their die-hard fans love most?

Monster Hunter Woes

Last time I wrote on this blog, I discussed my first ever experience playing a game in the Monster Hunter franchise. To briefly summarize, I played Monster Hunter Generations Ultimate, which was the last game in the franchise before the series was “casualized” for broader Western audiences with Monster Hunter World. My first experience with MHGU was one of frustration and agony: the game is front-loaded with hours of menial gathering quests and tedious tutorials, and when you finally get to fight monsters, your hours of mushroom gathering do nothing to help you.

To address the poor new player experience as well as many unintuitive aspects of the franchise, Capcom released Monster Hunter World. While this game streamlines the Monster Hunter experience and appeals to a wider audience, many of the original fans of the series are, to put it nicely, disappointed. MH World’s current roster of 36 large monsters pales in comparison to MHGU’s whopping 93 large monsters. Additionally, many iconic armor and weapon designs were either simplified or removed entirely in MH World.

And yet, despite all this, Monster Hunter World is the best-selling title in Capcom’s 40-year history. So, who’s correct? Unless you’re a business executive at Capcom, there’s no clear cut answer.

Authenticity: Cult Classics for a Reason

Many games need to lean heavily into the authenticity of the franchise. It is no exaggeration to say that many games would entirely lose their appeal if they tried to reach a wider audience. The Dark Souls series is famous in mainstream media because of its uncompromising difficulty, and it is even responsible for creating the “Souls-like” genre of uncompromisingly difficult games that punish you for dying. Other lesser-known franchises such the Touhou bullet hell series (video shown below) have such high barriers to entry that only the most dedicated players even stand a chance at completing the game.

Accessibility: Let Everyone Play

Other games try to be as accessible as possible. These games consistently reach larger audiences by smoothing out the experience to appeal to everyone. Consider the most recent additions to the longstanding Pokémon game series: Pokémon Sword and Shield. These games are designed to appeal to kids who have never played a Pokémon game as well as veterans who first played Pokémon over 20 years ago, so accessibility is top priority. These games received a lot of criticism for their lack of innovation and terrible online functionality, but they still broke Nintendo sales records and were responsible for massively boosting sales of the Nintendo Switch console. The developers at Game Freak probably figure, “Hey, we have a formula that works, why change it?” From a business perspective, it’s hard to argue with them, but longtime players of Pokémon games might be disappointed with how little fresh content there is to experience.

By the way, you could make a counterargument that the authentic Pokémon experience was designed for kids and prioritizes accessibility over almost anything else. However, if you go back to the roots of the franchise with the original Pokémon Red and Blue games on the Game Boy, I think you will find that these games are far more difficult and convoluted than recent entries in the series. Therefore, my point remains that the newer Pokémon experience is far more accessible than the “authentic” Pokémon experience of the older games.

Smashing Revelations

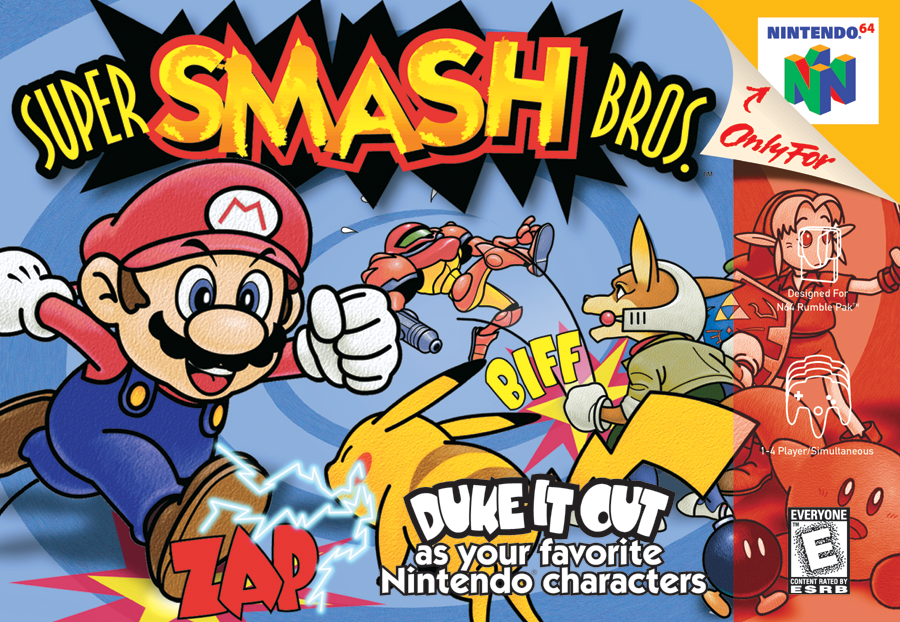

Rarely, there are some franchises that try to walk the thin line between staying true to the feel of the original games while keeping the series accessible to everyone. This is the case for the Super Smash Bros. game series, and with each entry, we can clearly see how the developers tried to both appease fans of the original games while keeping the game accessible to newcomers.

The original Super Smash Bros. was released for the Nintendo 64 in 1999. The director, Masahiro Sakurai, wanted to create a fighting game that was fun for fighting game enthusiasts such as himself but was still approachable for players who were unfamiliar with fighting games. The result was a unique blend between traditional 2D fighters and 2D platfomers that featured a simple control scheme but a high skill ceiling.

The sequel, Super Smash Bros. Melee, was released on the Nintendo Gamecube in 2001. This game featured faster gameplay with a much higher skill ceiling, and as a result, it accidentally fostered a cult following that still plays the game competitively nearly 20 years later.

However, the lightning quick gameplay (as shown in the video above) made the game inaccessible for new players. As a result, the game still struggled to find a broad audience.

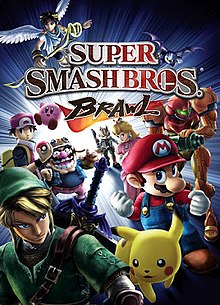

The next game, Super Smash Bros. Brawl, was released on the Nintendo Wii in 2008. To address the accessibility issues present in Melee, this game deliberately slowed down the gameplay and added random elements such as tripping to make the game more friendly to casual players. By trading authenticity for accessibility, these changes made Brawl the most successful entry in the series so far, but it alienated the players who enjoyed the competitive feel of the original games.

After Sakurai noticed that many hardcore fans still played Melee instead of Brawl, he designed Super Smash Bros. for Wii U (released 2014) to exist somewhere between the extreme speed of Melee and the casual pace of Brawl. This game was well received, but at this point, the damage had been done. The Melee players were committed to their game, and they hadn’t forgotten how they were betrayed by Brawl. The Melee players stuck with Melee, but newer players happily moved from Brawl to Wii U and found its faster gameplay exciting.

At last, in 2018, Super Smash Bros. Ultimate on the Nintendo Switch tried to live up to its name and bridge the great divide in the Smash community. This game features fast gameplay that appeals to the Melee players, and it also uses an input buffering system that ensures less experienced players can play at the faster pace without being frustrated by mistiming their inputs. This game had great reception overall: Wii U players saw it as a strict upgrade to their preferred game, and Melee players conceded that the game was at least fun to play. However, it still wasn’t enough to unify the community. To this day, Melee and Ultimate are both played competitively in separate tournament brackets. Despite his best efforts, Sakurai could not totally appeal to players on both sides of the authenticity versus accessibility spectrum. Could he have done anything better?

There’s No Right Answer

While you can easily point to Brawl as the wedge that split apart the Smash community, you can’t say that Brawl was a mistake. The game was a massive commercial success, and it led to later entries that newcomers to the franchise absolutely loved. However, this came at the cost of permanently alienating the original fans of the game series that helped it get off the ground.

So, what’s the right answer? Should game franchises prioritize authenticity or accessibility? Honestly, I’m not sure. Shooting for accessibility certainly seems like the better option from a business perspective, but building a good rapport with your game’s community is equally important. Ultimately, the best advice I can give is that game designers should keep both perspectives in mind when designing their games.